Should the public broadcaster have discretion to reject a political advert?

Regulator's complaints committee hears argument on SABC's refusal to broadcast Democratic Alliance TV advert

Back in the day - sometime in 1993 - I was a thirty-something media activist (with an ill-fitting suit). Despite my questionable dress sense, I was selected by anti-apartheid civil society groups and the African National Congress (ANC) to be one of the drafters of the Independent Broadcasting Authority (IBA) Bill - a law that would form part of a package of laws negotiated and agreed to usher in South Africa’s democracy.

The IBA Act was passed in 1993. It became foundational to our broadcasting framework, and was a radical change from the apartheid state's total, authoritarian control over broadcast regulation. The Act established the IBA with a range of progressive statutory provisions, including community radio licences, quotas for on-air SA content, black empowerment licensing provisions, and a whole new system for regulating party election broadcasts and political advertising during election periods.

Kempton Park, Johannesburg 1993. Me with an ill-fitting suit outside the ill-fittingly named venue of South Africa’s constitutional negotiations. I attended these meetings as a member of a technical committee which drafted the Independent Broadcasting Authority Bill. Picture credit: Steve Hilton-Barber

Fast forward to #SAElections24 - the interpretation of the law on political advertising has now been disputed for the first time after the SABC rejected a political advert from the Democratic Alliance (DA). The television ad itself was offensive to many South Africans. It depicted the burning of our national flag as part of a fear mongering narrative to depict what would happen if the ANC was returned to power. The flag was then shown to be ‘made whole’ if the ANC was voted out.

The ad caused widespread outrage as the national flag had become a respected, unifying symbol of our three decade old democracy. President Cyril Ramaphosa and government ministers issued strong statements against the advertisement, with threats of court action. President Ramaphosa said the ad was "treasonous and despicable". Minister of Sport, Arts and Culture Zizi Kodwa said the ad was “a desecration of a national symbol” and that the government was considering its legal options. Despite all the sound and fury, my view was that, despite the advert being divisive, provocative, in poor taste and offensive, the ad itself constituted lawful political expression.

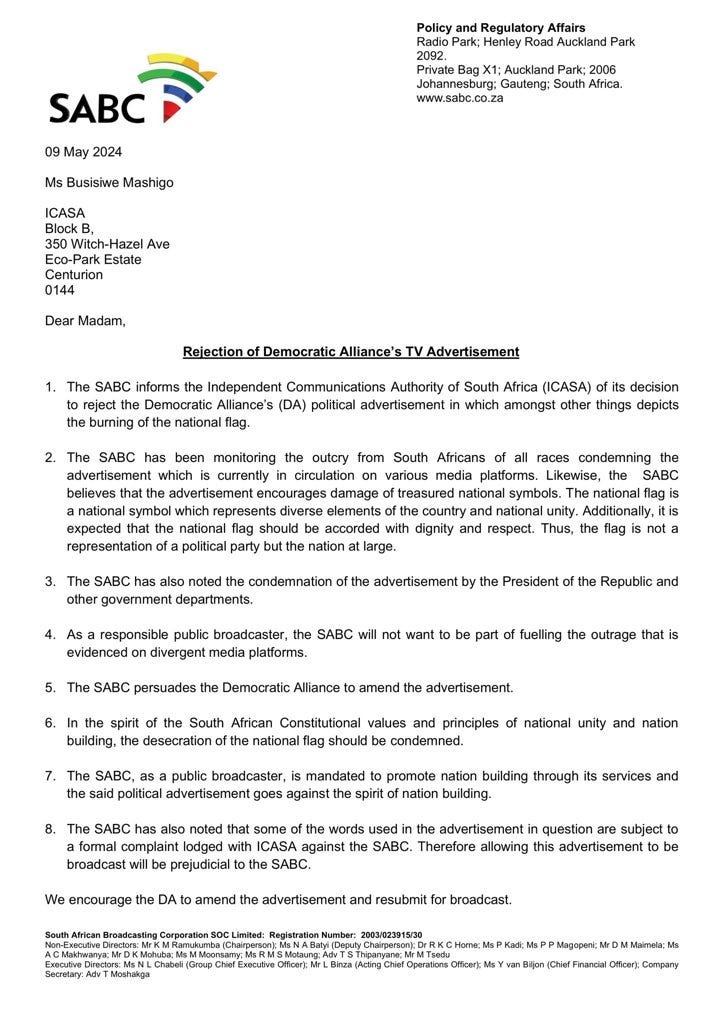

Shortly after statements by the President and Minister Kodwa, on 9 May 2024 the SABC issued a statement saying they had rejected the political advertisement for reasons that appeared questionable and (as required by law) had notified the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA), the IBA's successor regulator.

Source: SABC letter to ICASA on 9 May 2024

In response to the rejection of their television ad, the DA then submitted a formal complaint to ICASA’s Complaints and Compliance Committee (CCC). On 17 May oral argument was made by counsels for the SABC and the DA, battling each other over the meaning of the law. With the election just over 10 days away this is clearly an urgent issue and ICASA agreed to come back with a decision by 20/21 May.

The main disputed clause in question was section 58(1) of the Electronic Communications Act, 2005 - a provision which had been largely ‘copied and pasted’ from the IBA Act of 1993.1

"58(1) A broadcasting service licensee is not required to broadcast a political advertisement, but if he or she elects to do so, he or she must afford all other political parties, should they so request, a like opportunity" (my emphasis).

The intention of the legislature in 1993 was very simple: section 58(1) did not compel broadcasters to carry political ads but if a broadcaster decided to carry political advertisements for one political party then they had to give other political parties "a like opportunity". The SABC’s argument for an inherent right to reject political ads would work if section 58(1) ended with a full stop after “advertisement” but it doesn’t.

As one of the original drafters of this provision 30 years ago, the question is should the provision have been improved and made clearer over the years? The answer is obviously yes. In fact, I have written here before that the entire broadcasting framework is outdated and mostly archaic. However many industry legal experts agree that section 58(1) still does not give SABC an inherent right to refuse to broadcast a political ad and certainly not for the reasons advanced by the public broadcaster (in the letter to ICASA.)

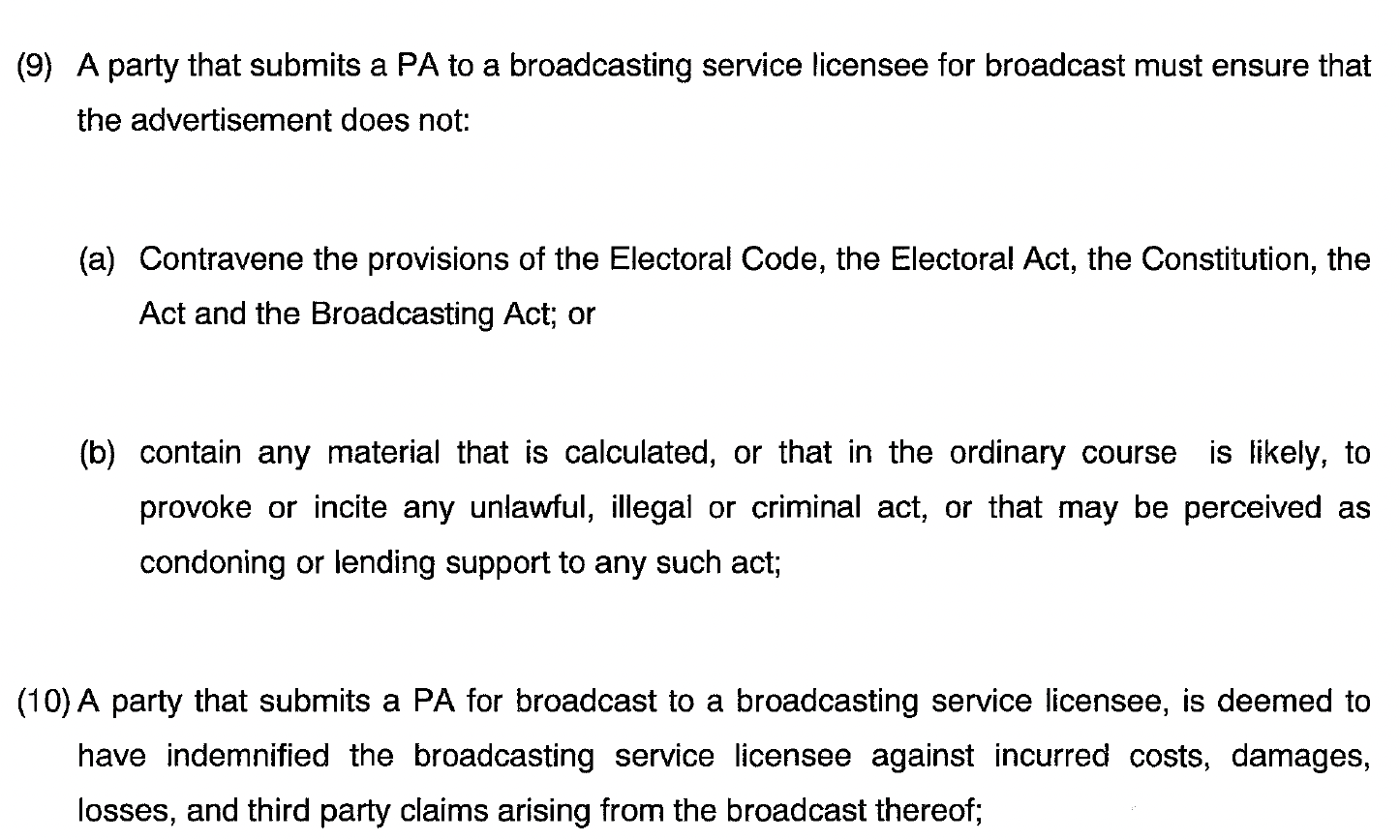

The regulations make it even clearer that the onus is on the political party, not the broadcaster, to ensure the content does not breach the law or incite “unlawful, illegal and criminal acts.” In addition, broadcasters are indemnified from any legal liability for party political adverts broadcast on their platforms.

Source: ICASA’s National and Provincial Party Election Broadcasts and Political Advertisement Regulations, 2014

But during oral argument on 17 May it became clear that the SABC was not claiming that the advert was unlawful or fell foul of the regulations. It claimed an inherent right to reject the ad because, amongst other reasons, the SABC was responsible for “nation building” and the DA’s “political advertisement goes against the spirit of nation building”.

The SABC made a number of other debatable legal arguments, the most striking being that ICASA does not have the remedial power to compel SABC to broadcast the DA’s ad. Despite agreeing that ICASA had jurisdiction over the dispute, the SABC’s counsel argued that SABC’s decision was an administrative act and only a court of law could order SABC to broadcast the ad. This position seems to be at odds with the legislation and regulations which created a very specific framework for political ads during elections, including a dispute resolution process. Why set up this elections-specific framework under ICASA’s jurisdiction if only a court could order remedial action?

These questions will no doubt be answered soon. While the disputed legal provisions have survived the last 30 years, my suits are still ill-fitting for more weighty reasons!

I look forward to the ICASA CCC’s final decision and the ICASA Council’s implementation of the ruling. I also hope that the matter is not ligitated in the courts and can be resolved before the election on 29 May 2024.

In 1993 political ads were only allowed on sound (radio) broadcasters and this was later broadened to include political adverts on television. Apart from this, section 58(1) of the ECA, 2005 is exactly the same as the original language of section 60(1) of the IBA Act, 1993: “A sound broadcasting licensee shall not be required to broadcast a political advertisement, but if he or she elects to do so, he or she shall afford all other political parties, should they so request, a like opportunity”.

It's all electioneering. The DA meant to provoke but instead gave the ANC and others a press victory. The irony is none of them care about our country, and nationalism is almost dead in the Public mind. People and politicians aside, it shouldn't have been banned. And I say that as someone who despises the DA.